The Origins of Shading – How Darkness Changed the Taste of Tea

Although it cannot be confirmed with absolute certainty, it is widely believed that the earliest shading structures were originally introduced to protect delicate young tea buds and leaves from frost. Their influence on flavour was, at first, merely an unintended side effect.

When deprived of sunlight, tea plants trigger a cascade of physiological responses in order to adapt to lower light conditions. They begin producing higher levels of chlorophyll, amino acids and caffeine, while reducing the formation of catechins.

The result? Leaves that are deeper green, richer in umami, naturally sweeter, and less astringent.

What began as protection from cold gradually became one of the most refined cultivation techniques in Japanese tea history.

A Brief History of Shading

Pinpointing the exact origins of shading is difficult. While bamboo and straw structures became common in the Uji region during the second half of the 16th century, modern soil analyses suggest that such practices may have existed as early as the beginning of the 15th century.

In 1577, the Portuguese missionary João Rodrigues Tsuzu described seeing covered tea plantations near the town of Uji, in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture.

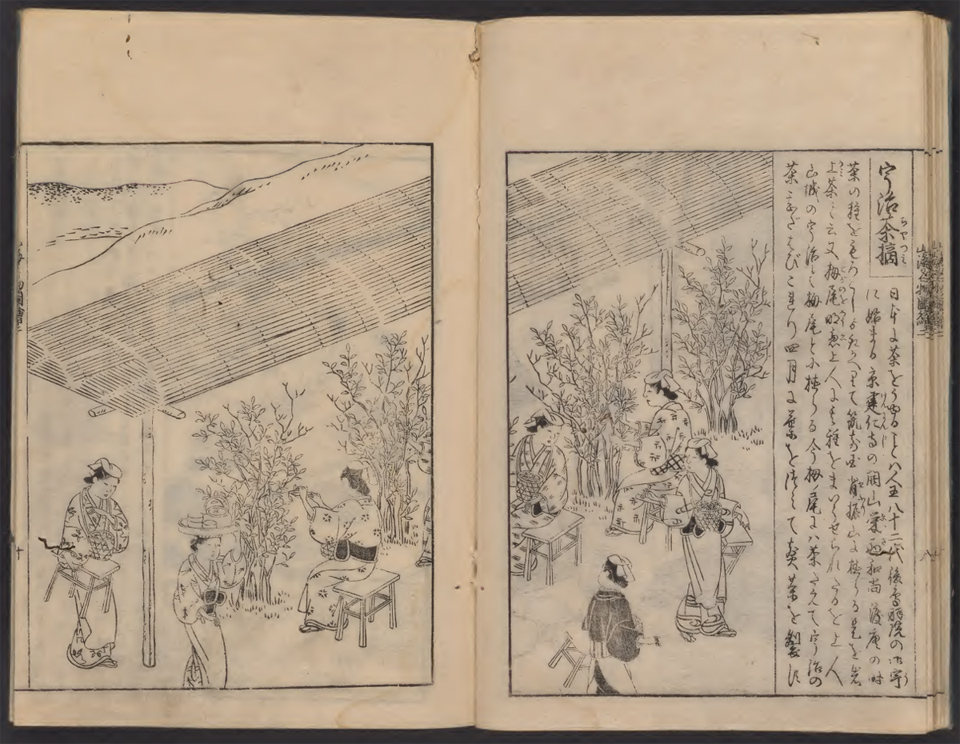

Later, in 1797, the illustrated book Nihon Sankai Meibutsu Zue (日本山海名物圖會), translated as Famous Products of Japan’s Mountains and Seas, depicted the harvesting of shaded tea leaves in the Uji region. By then, shading was no longer experimental — it was a defining element of high-quality tea production.

Timing and Techniques of Shading

The exact timing of shading varies from farm to farm, but it generally begins between the appearance of the first bud and the development of the first leaf.

Over the centuries, several shading methods have evolved in Japan: Jikakabuse, Kanreisha, and Honzu. Each has its own characteristics, advantages and limitations — and each influences the appearance and flavour profile of the tea leaves.

Jikakabuse (Direct Covering of Tea Bushes)

This is the simplest and most economical method. A black synthetic cloth is placed directly over the tea bushes.

During the first seven days, the initial layer blocks around 70% of sunlight. Even within this short period, the leaves begin developing a brighter colour and deeper flavour typical of shaded teas.

After about a week, a second layer may be added, increasing light blockage to approximately 90–95%.

This method is commonly used for Kabusecha (partially shaded sencha). After roughly two weeks, the growing leaves touch the fabric and can no longer expand freely. They are then harvested and processed in the same way as sencha. Thanks to shading, Kabusecha develops a sweeter, fuller body and noticeable umami due to its higher amino acid content.

Kanreisha (Shading with Synthetic Fabric Over a Structure)

Today, this is the most widely used shading technique. Instead of placing the cloth directly on the plants, it is stretched over a structure built above the tea bushes.

This allows better air circulation and moisture control, enables freer leaf growth, and permits longer shading periods.

The first layer blocks approximately 70% of sunlight for 7–10 days. Once two additional leaves have developed, a second layer with 90% shading capacity is added. Combined, they reduce sunlight by 95–98%.

The tea bushes remain under shade for 3–4 weeks before harvesting. This method is commonly used for producing leaves intended for Matcha (Tencha) and Gyokuro.

Honzu (Traditional Reed and Straw Shading)

Honzu is the original and most traditional shading method, dating back more than 400 years.

A wooden or bamboo frame is constructed above the tea bushes. Reed screens form the first layer, and rice straw or straw mats are placed on top.

For the first 7–10 days, the reed layer blocks approximately 60–70% of sunlight. After two additional leaves develop, a layer of rice straw is added, reducing light exposure to around 90–92%. The bushes remain shaded for about five days before a second straw layer is added, achieving 95–98% shading. They stay covered for another 7–10 days before harvest.

Fresh straw plays an essential role in the Honzu method. Rich in minerals, it gradually decomposes and nourishes the soil, contributing to the distinctive, complex flavour profile of Hon Gyokuro.

Historically, Honzu was widely used for producing leaves destined for Matcha (Tencha) and Gyokuro. Today, however, it has become increasingly rare due to the intensive manual labour it requires.

For the Curious Tea Drinker

Today, more than 90% of Gyokuro gardens are shaded using black synthetic cloth — the Kanreisha method.

The designation Hon Gyokuro, however, is reserved exclusively for tea produced from gardens shaded with traditional straw. The word “Hon” (本) in Japanese means “true” or “authentic”.

In our selection, you will also find GYOKURO from the YAME region proudly bearing the designation "HON" — a tribute to the most traditional and demanding form of shaded tea cultivation.